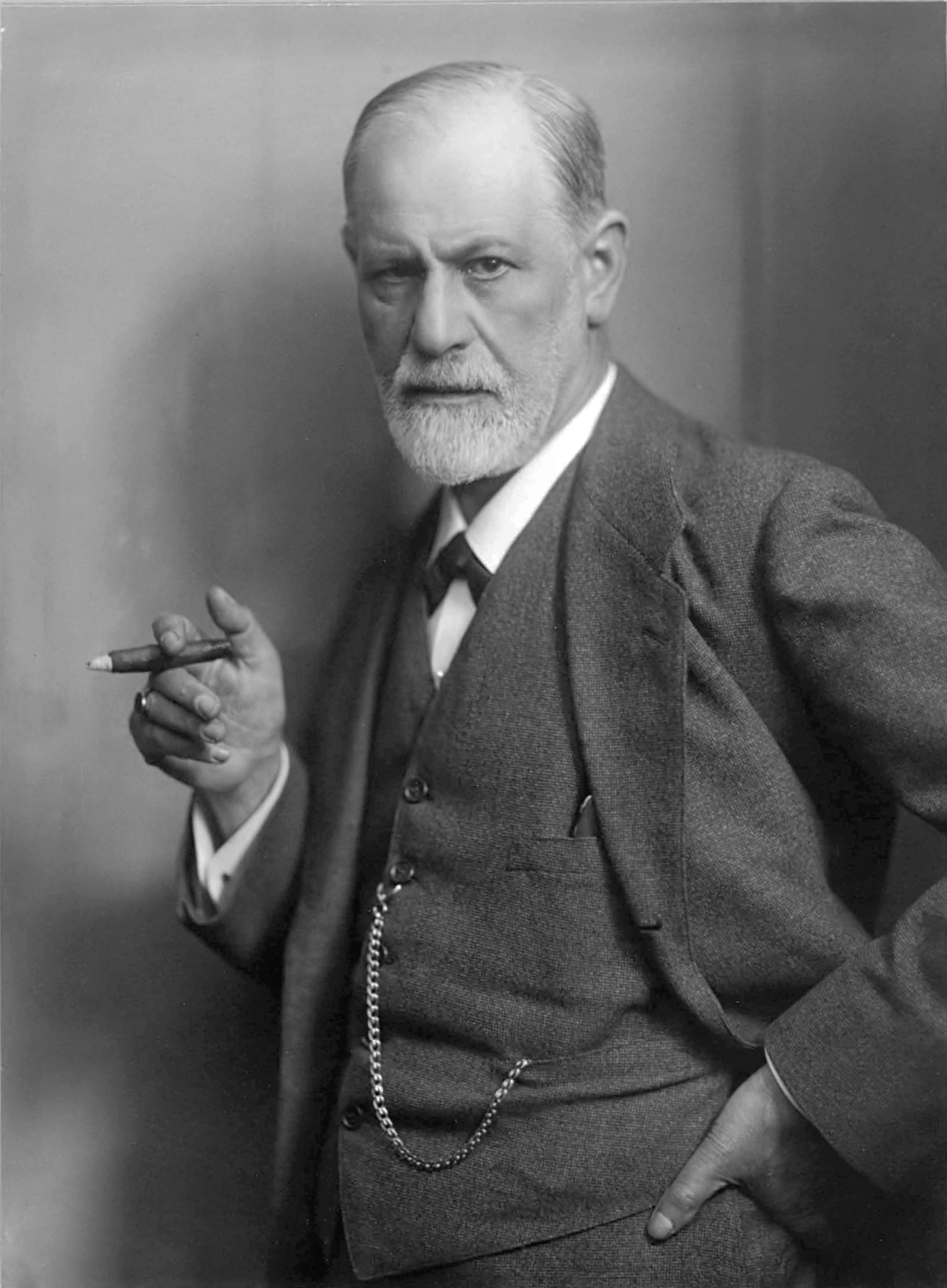

Sigmund Freud, ca. 1921

By Grant Holt

Far from a trivial hobby of his youth, cocaine represented Sigmund Freud’s first independent efforts to alleviate psychological suffering. He published multiple papers on the drug—believing it to be a miraculous cure for misery—but his expectations fell short. Freud prescribed cocaine to his family, friends, and colleagues—resulting in the expedited decline of at least one of them. Freud soon suffered the condemnation of the medical community for unleashing a new horror upon the world. Nevertheless, cocaine allowed Freud to try to treat mental illness early in his career, paving the way for his later theories of psychoanalysis.

The neuroses that Freud struggled with—and later tried to alleviate—have roots in his childhood. His grandfather, his younger brother, and his beloved nanny died by the time he was four years old. His father’s financial troubles left Freud’s family impoverished. When Freud qualified as a doctor in 1881, he preferred to research brain anatomy, but failed to secure a research job at the University of Vienna. His impoverished background left him no choice but to practice clinical medicine. In 1882, Freud met his fiancée, Martha Bernays. They were engaged two months later. With his life coming together, Freud needed a discovery to establish his reputation and ensure financial stability. He found it one year later while reading a medical journal.

In 1883, German physiologist Theodore Aschenbrandt enlisted in the Bavarian army as a surgeon. While marching with his brigade one hot day in 1883, a soldier collapsed from exhaustion. Using cocaine from the pharmaceutical company Merck, Aschenbrandt administered a tablespoon of water with drops of a cocaine solution. After five minutes, the soldier stood up and continued to march easily. Aschenbrandt later suffered a sleepless night. Upon waking, he mixed cocaine into his morning coffee and for the rest of the day felt completely energized. Aschenbrandt soon published his findings in a German medical journal—which Freud read.

Fascinated, Freud placed an order for one gram of pure 98% cocaine hydrochloride from Merck. Freud first experienced the miraculous effects of cocaine on April 30, 1884. Freud drank 0.05 grams of cocaine in a solution of water. A few minutes later, Freud felt rejuvenated. He wrote that he enjoyed these results without any unpleasant side effects. Freud asserted that he felt no craving for the further use of cocaine, and that he instead felt an aversion to it.

Whenever Freud took cocaine, he almost always consumed the drug orally. Administered orally, the body metabolizes cocaine at a much slower rate than if it was, for instance, injected into the veins. The effects of cocaine are also dispersed over a longer period of time. Freud did not experience the typical burst of euphoria when it is injected or smoked. Consequently, Freud’s oral cocaine use might have caused him to underestimate its effects.

Nevertheless, this first experience with cocaine mitigated Freud’s depression and fatigue. Over the next couple months, Freud tested cocaine a dozen times. He administered cocaine to his friends, colleagues, patients, and—most importantly—himself. The drug worked for him, and this made cocaine worth studying. Freud plunged into research, finding everything he could read about cocaine. Despite finding a few negative accounts of the drug, Freud did not read about any concrete damage to people taking cocaine.

During his initial research, Freud came across evidence of cocaine treating morphine addicts. He found a journal article published in the September 1880 edition of the Detroit Therapeutic Gazette. Titled “Erythroxylon Coca in the Opium and Alcohol Habits,” the article described four different cases where cocaine reduced or even eliminated the patient’s need for morphine within two years. Freud took special notice of these results. His close friend, teacher, and colleague—Ernest von Fleischl—developed an addiction to morphine after a workplace injury. After reading this article, Freud believed that cocaine could help him.

A German physiologist, Fleischl injured himself during an autopsy. He sliced his thumb during the operation, which shortly became infected. Fleischl lost the thumb. After amputating it, Fleischl developed excruciating chronic pain as neuromas—or, nerve tumors—grew around the amputation site. In order to manage his pain, Fleischl turned to morphine. By 1884, the young physiologist was wholly addicted to regular morphine injections. This troubled Freud, and nine days after taking cocaine for the first time, he prescribed it to Fleischl.

Ernst von Fleischl, ca. 1890

Allegedly, Fleischl stopped using morphine and took only cocaine for three days. Although he did not monitor Fleischl’s treatment, Freud reported that cocaine prevented symptoms of morphine withdrawal, like diarrhoea, depression, and—of course—a craving for morphine. But according to Freud, Fleischl experienced none of them.

Freud planned to write about his studies, expecting cocaine to become a quality therapeutic drug. Freud sincerely believed that cocaine cured a morphine addict.

Unfortunately, Freud’s cocaine therapy did the exact opposite. Fleischl’s condition grew increasingly worse. Just five days after starting Fleischl’s treatment, Freud’s ability to enjoy cocaine’s successes were hampered by Fleischl’s worsening condition. Fleischl continued to take cocaine, but he soon developed convulsions that left him nearly unconscious. By the end of May, cocaine had clearly failed to cure Fleischl’s addiction. But Freud did not see it that way. He blamed Fleischl for taking cocaine in enormous quantities. Freud convinced himself that cocaine failed only because Fleischl took too much of it.

His faith in cocaine unscathed, Freud turned his attention to publication. In July of 1884, Freud published his first paper on cocaine. Titled “Über Coca,” the paper dissected the coca plant and its biological processes, outlined how Spanish explorers first encountered Indigenous coca leaf chewers in South America, and proposed some therapeutic applications of cocaine. Among these applications, Freud suggested using cocaine to treat addictions to morphine. Freud concluded his paper with a brief paragraph, in which he mentioned that cocaine had an anesthetizing effect when applied onto the skin. He did not realize it at the time, but Freud accurately listed the one lasting medicinal application of cocaine—local anesthesia.

Had Freud pursued cocaine as a local anesthetic, he would have achieved the fame and financial stability he craved. But after publishing his paper, Freud left for the city of Hamburg to visit his fiancée. He had not seen Martha in two years. During his absence, the ophthalmologist Carl Koller read “Über Coca,” and was inspired.

Koller tried cocaine orally, and noticed that it numbed his tongue. Believing that this drug could be a local anesthetic, Koller immediately went to the laboratory in order to test the effects of cocaine for himself. In August of 1884, he officially discovered cocaine as the first ever local anesthetic. Koller quickly rose to medical stardom, leaving Freud behind as a mere footnote.

Despite this, Freud remained on friendly terms with Koller. Freud did not claim credit, and instead declared that Koller had the idea of using cocaine as an anesthetic. In fact, when reflecting on this missed opportunity in later years, Freud actually attributed his oversight to his fiancée. Freud simply reconciled with the fact that he had missed the discovery. He accordingly resumed his cocaine studies.

Freud published more papers preaching the therapeutic power of cocaine. He particularly recommended cocaine for the treatment of neuroses. In early 1885, Freud published “Contribution to the Knowledge of the Effect of Cocaine,” a paper concerning the internal effects of cocaine. He discussed a study in which he measured the power of cocaine to create an elevated mood, and increased physical and mental endurance. Freud wrote that cocaine stimulated certain muscles and impacted reaction time. His desire to use cocaine to treat psychological conditions like depression and weakness sprouted from Freud’s continued struggle with both.

Freud’s career was difficult. He gave up an academic job after pursuing it for six years. In its place, Freud prepared himself for a job at the Vienna General Hospital that he did not care for. His separation from his fiancée for years left him emotionally frustrated. Cocaine fixed this. Unlike alcohol, this drug elevated Freud’s mood and boosted his productivity. This effect gave him an important insight—that an unknown psychological factor hampered a person’s well-being, and that cocaine treated it.

The rising demand for cocaine dropped suddenly around 1886. Even Freud stopped experimenting with the drug. There were a few reasons for this—like starting his private medical practice and marrying his fiancée—but chief among them were the countless reports of patients developing a severe addiction to cocaine.

These reports excluded Freud. Despite his continued use of cocaine, Freud did not develop a serious addiction. Fleischl, however, did. After six months of cocaine, Fleischl continued to deteriorate. He experienced mood swings, convulsions, and insomnia. Fleischl’s tolerance to cocaine grew and resulted in greater doses. In 1885, he developed a drug-induced psychosis, and his symptoms were graphic. While suffering delirium tremens, he hallucinated white snakes creeping all over him.

Such symptoms could only be the product of heavy cocaine use. At this point, Fleischl injected into his veins one whole gram of pure cocaine every day. Fleischl consequently became one of the first morphine addicts to be “cured” by cocaine, and subsequently one of the first cocaine addicts in Europe.

By 1886, cocaine addicts were reported all over the world. Germany, in particular, had a huge sense of alarm about cocaine. Nobody better articulated the panic and dread of cocaine more than German physician Albrecht Erlenmeyer, who condemned Freud and his cocaine for unleashing, in addition to morphine and alcohol, “the third scourge of humanity.” Just three years after his first dose of cocaine—and just one year into his private practice—Freud faced condemnation for unleashing a new kind of terror on the world.

But Freud refused to admit his mistakes. In July of 1887, Freud published his defense. His 1887 paper “Craving For and Fear of Cocaine” defended the drug against accusations of addiction and harm. In the paper, Freud did not blame cocaine for inducing addiction. He asserted that all patients who fell into cocaine addictions were already addicted to morphine. He explained that he took the drug himself for months without the formation of addiction, and in fact developed an aversion to cocaine. Freud did admit that, depending on the person, cocaine’s effects fluctuated. After this paper, Freud did not publish another major article on cocaine. His contemporaries did not change their minds. Cocaine vanished from psychiatry, and in time was even replaced by non-habit-forming methods of local anesthesia.

Fleischl died six years later in 1891. Had Freud not intervened, Fleischl’s condition would likely have deteriorated anyway. Cocaine merely expedited his decline. Freud did not kill Fleischl, but he certainly did not heal him. Years later, Freud reflected that treating morphine addiction with cocaine was “like trying to cast out the Devil with Beelzebub.” At the time, however, Freud stubbornly refused to believe this. When he stated that he experienced an aversion to cocaine—and not a craving—Freud prioritized this singular fact over everything else. He hesitated to recognize that his own experience was not the rule, but the exception. This rightly stigmatized his work as unscientific. However, without this belief in the experience of the individual, it is hard to imagine Freud ever developing his personalized theory of psychoanalysis. Through cocaine, Freud started to think on a psychological level. This drug bridged the gap between Freud’s physiological work and psychological work, setting the stage for his later psychoanalytic theories. Cocaine continued to influence him past 1887 and into the future, as demonstrated when cocaine materialized in Freud’s seminal psychoanalytic text, The Interpretation of Dreams.

In the first dream of the book—Irma’s Injection—Freud subjects his cocaine studies to psychoanalysis. In the dream, Freud peers into his patient Irma’s throat and sees scabby nostrils, reminding him about his own health. He explains that he suffered from nasal swellings, and used cocaine to treat them. Freud mentions that he was the first to recommend the use of cocaine, and that it resulted in the expedited death of his friend, Fleischl. Later in the dream, Freud states that Irma received medicinal injections. This again reminds him of Fleischl, who immediately gave himself injections of cocaine. Freud judged the recurrence of cocaine, along with Irma’s health and his own ailments, to be his latent concern to restore the well-being of his patients. Years after this drug failed to help his patients, Freud remembered cocaine in a dream that manifested his desire to alleviate suffering. His desire for cocaine to become a cure never materialized. With this in mind, Freud concluded his analysis with a fundamental tenet of psychoanalysis—that a dream is the fulfillment of a wish.